One of the more exciting moments in reading is coming across texts that show a writer’s own reading creeping into their writing. In my own work, I can think of an orange I inadvertantly stole from a Gary Soto poem as well as a prayer reformulated from an Ernest Hemingway short story. These are moments where an influence is unavoidable or inevitable in hindsight. Not outright theft but more moving forward with one’s influences like burrs caught on your clothing after walking through grass.

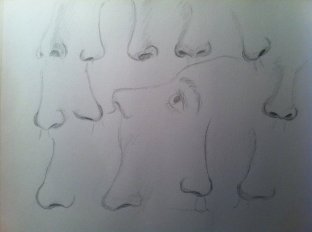

I found such a moment in reading William Carlos Williams recently. While I’ve long admired his poem “Smell” for its ingenuity and directness, learning that he had translated the work of the Spanish Gold Age writer Francisco de Quevedo added another layer of meaning. Quevedo has an infamous sonnet, an “ode” to a rival’s nose, that, when read with Williams in mind, can’t help but conjure up the latter’s own poem. Here are excerpts from Quevedo’s sonnet, “A Una Nariz” (To a Nose):

I found such a moment in reading William Carlos Williams recently. While I’ve long admired his poem “Smell” for its ingenuity and directness, learning that he had translated the work of the Spanish Gold Age writer Francisco de Quevedo added another layer of meaning. Quevedo has an infamous sonnet, an “ode” to a rival’s nose, that, when read with Williams in mind, can’t help but conjure up the latter’s own poem. Here are excerpts from Quevedo’s sonnet, “A Una Nariz” (To a Nose):

Érase un hombre a una nariz pegado,

érase una nariz superlativa,

érase una nariz sayón y escriba,

érase un pez espada muy barbado.

…

Érase un naricísimo infinito

frisón archinariz, caratulera,

sabañón garrafal, morado y frito.

(Once there was a nose with a man attached,

a superlative nose,

a nose both criminal and scribe,

a swordfish with an overgrown beard.

…

It was an infinity of nostrilisticity,

a towering archnose, a mask,

a proud and painful protruding pimple.)

One can see the exaggeration and wordplay of Quevedo’s original influencing Williams’ poem below. While the speaker in the poem by Williams turns the satire on himself, there is no less enthusiasm and barb in his words. Considering the two poems together, I can’t help but view the question asked in the last line of the Williams poem (Must you have a part in everything?) as mirroring the way reading influences writing.

Smell – William Carlos Williams

Oh strong-ridged and deeply hollowed

nose of mine! what will you not be smelling?

What tactless asses we are, you and I, boney nose,

always indiscriminate, always unashamed,

and now it is the souring flowers of the bedraggled

poplars: a festering pulp on the wet earth

beneath them. With what deep thirst

we quicken our desires

to that rank odor of a passing springtime!

Can you not be decent? Can you not reserve your ardors

for something less unlovely? What girl will care

for us, do you think, if we continue in these ways?

Must you taste everything? Must you know everything?

Must you have a part in everything?

*

Happy nosing!

José