review by José Angel Araguz

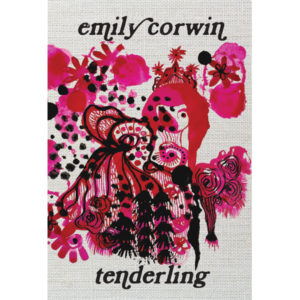

Looking up definitions of the title phrase to Emily Corwin’s tenderling (Stalking Horse Press, 2018), I found three meanings: one definition refers to one who has been coddled, or one who is weak or effeminate; the second has the word “tenderling” refer to a little child; and the last to one of the budding antlers of a deer (source). I find the juxtaposition of these definitions fascinating, particularly the pronounced mix of weakness and affection in the first two, and the nod towards strength and protection in the third. The poems in Corwin’s collection reflect a sensibility capable of interrogating each facet of these definitions, challenging the perceived weakness of illness while subverting the world of children’s stories and fairy tales, all while presenting the fact of the poem as a space where strength and imagination can bud and flourish.

In “tantrum,” for example, the uncontrolled outburst of anger implied in the title is seen as a mirror able to reflect back not a self but a slip of self that overwhelms:

at first, this terrible mirror, gutted. it is thinking of taking me.

at midnight, screaming illness, I fill a particular dark. I rustle, I

thrash—a girl loose in the bramble, getting wretched, smashing

up a glass syringe. how to return this rage, how it circles endless

—like bruise, like stone too black. I get hurt in you, becoming

skeleton. my ruffles everywhere, wilting.

The mirror metaphor here is far from passive; aligned with the idea of a tantrum, the mirror becomes an active part of the outburst, threatening to redefine the speaker. Succumbing momentarily, the speaker “fill[s] a particular dark” and is witness to seeing herself as “a girl loose in the bramble.” This slip of self creates a desire “to return this rage,” a desire which ultimately goes unfulfilled, but which in itself is revelatory. As mirrors in fairy tales often serve as passageways to other worlds, what matters is ultimately getting back home. Here, getting back entails not home but the self, and also naming what was experienced, the “hurt” and the “wilting.”

The work of naming experience is done here and elsewhere through attention to the fluidity of language. As with the multiple meanings of the word “tenderling,” this collection consistently engages with language for its variety as much as for its veracity of feeling. The opening of “split oak,” for example, makes compelling use of anagrams:

you felt me, you left me — moaning open in a landslide.

Having this three word phrase turned on its head with a quick shuffle of letters creates dramatic tension in a poetic way, concisely evoking two sides of a relationship. Yet, beyond the wordplay, it is meaningful to emphasize how the word implying intimacy (“felt”) is made up of the same letters and thus holds the word implying that intimacy’s end (“left”). Later, in the poem “torn,” the speaker notes

how you can’t spell slaughter without laughter,

bringing these words together in a way that evokes urgency and intimacy mixed with threat. In this way, tenderling makes its case for language as a kind of bramble, one from which identity and relationships work at turns to free themselves from and lose themselves in.

Corwin’s poetic sensibility remains engaging throughout tenderling because of this complex relationship with language. Words and fairy tales alike are repurposed and reclaimed in poems that point to something beyond themselves. There are no simple retellings here; rather, what occurs in these poems is more akin to resurfacing, language and self coming up for air.

In “abacus” (below), the metaphor of a mirror returns, only here its counterpart is a smartphone. The way the self is complicated and reflected across glass and social media apps is meditated upon, until the language of technology and relationships merge in a moment of bittersweet awareness.

*

abacus – Emily Corwin

I use my phone as a mirror. I have zero likes. I like

mud-rose & jewelweed & you. you left my body cells

astonished. I am missing you something fierce in these

greenfields & oil fields & fields of scary love I do not like.

such a long way from this little while together. with you,

it is a presence or absence of claws — your hands that might

injure. desire holds me like a knife. what do you want me to

say to that? you say back. I research what larger animals are

most likely to kill me in the surrounding areas — most likely

horse or dog — & you think my hair is alive & it is. I get so

impossible with emotion, blighted, startled like a starling.

I order the latest version of a cave — tight, dripping — where

I can disappear into. I remember we enjoyed getting down

low in the bull thistle, downloading each other. you sent:

remember this? in your message request. the attachment

failed to load, inside the glow screen, silken.

*

Influence Question: How would you say this collection reflects your idea of what poetry is/can be?

Emily Corwin: I believe that the shape of the poem on the page is just as important the content. A poem’s form is its container, and that container provides information to the reader about what kind of speaker this is, the pacing of the line, the breath. Form lends physicality to our encounter with a poem. So, in tenderling, and in all my work, I like to experiment with shapes. This collection came from the first two years of my MFA at Indiana University, during which I was really into prose poems. There was a cleanness, a precision to that shape which I liked—the prose poem as a container felt tidy and orderly, juxtaposed with the sprawling, listing, anxious, messy quality of the voice in these poems.

There are lots of poems out there which re-adapt fairy tales, which play with themes of witchcraft, magic, femininity, dark woods, bodily transformation. This is a familiar set of images—however, my particular slant on these images concerns mental illness, chronic pain, and morbidity. I have a hip impingement on my right side, which causes me daily pain and discomfort. The cartilage between my hip bone and socket has essentially been worn away over time, most likely from my years as a ballet dancer. I also have misaligned ankles, for which I have to wear orthotics, as well as a generalized anxiety disorder highly focused on sudden and violent deaths.

After being diagnosed with these conditions—both physical and psychic—I was drawn to gurlesque poetics as a potential aesthetic for my work. Gurlesque aims to “enact, signs, bodies and psyches in crisis” (Lara Glenum, “Welcome to the Gurlesque: The New Grrly, Grotesque, Burlesque Poetics”). I want to demonstrate those crises, but not in such a way that the reader will leave the poem feeling despair. My intention is to show that it is possible to live with pain and beauty simultaneously, a life that is grotesque and lovely too. I think this is how the fairy tale as a genre works for me—the fairy tale is a space filled with irregular bodies and bodies in transformation—fairies, giants, unicorns, mermaids, princes and princesses turning into wild animals like swans, frogs, beasts. I imagine that in a fairy tale world, my body and brain would fit, in all its irregularities, conditions, illnesses.

Influence Question: What were the challenges in writing these poems and how did you work through them?

Emily Corwin: My struggle with this book is the same struggle I have always. I am an inherently impatient writer and reader—I think the reason I was drawn to poetry in the first place is because it’s short, it’s concise. I really struggle with prose. As a poet, I write fast and prolifically, which can be good, but also means that sometimes I rush (or I worry that I rush) through editing and submitting my work. James Reich, at Stalking Horse Press, has been excellent with catching things I missed when I first submitted the manuscript, with making changes that I suddenly needed, with being so kind and thoughtful throughout this process. I am consistently hard on myself and it helps to have an editor who is encouraging, who believes in the work and in me. I think I will always be impatient with myself, but surrounding myself, especially in the last year, with a community that I trust has made me feel okay, has helped me to let go of some of my anxious obsessing and to move forward with the next project.

*

Special thanks to Emily Corwin for participating! To find out more about Corwin’s work, check out her site. tenderling is available for pre-order from Stalking Horse Press.

Emily Corwin is an MFA candidate in poetry at Indiana University-Bloomington and the former Poetry Editor for Indiana Review. Her writing has appeared or is forthcoming in Black Warrior Review, Gigantic Sequins, New South, Yemassee, THRUSH, and elsewhere. She has two chapbooks, My Tall Handsome (Brain Mill Press) and darkling (Platypus Press) which were published in 2016. Her first full-length collection, tenderling is forthcoming in 2018 from Stalking Horse Press. You can follow her online at @exitlessblue.

Emily Corwin is an MFA candidate in poetry at Indiana University-Bloomington and the former Poetry Editor for Indiana Review. Her writing has appeared or is forthcoming in Black Warrior Review, Gigantic Sequins, New South, Yemassee, THRUSH, and elsewhere. She has two chapbooks, My Tall Handsome (Brain Mill Press) and darkling (Platypus Press) which were published in 2016. Her first full-length collection, tenderling is forthcoming in 2018 from Stalking Horse Press. You can follow her online at @exitlessblue.

Jenny Sadre-Orafai is the author of Malak and Paper, Cotton, Leather. Recent poetry appears in Cream City Review, Ninth Letter, The Cortland Review, and Hotel Amerika. Recent prose appears in Fourteen Hills and The Collagist. She is co-founding editor of Josephine Quarterly and Associate Professor of English at Kennesaw State University.

Jenny Sadre-Orafai is the author of Malak and Paper, Cotton, Leather. Recent poetry appears in Cream City Review, Ninth Letter, The Cortland Review, and Hotel Amerika. Recent prose appears in Fourteen Hills and The Collagist. She is co-founding editor of Josephine Quarterly and Associate Professor of English at Kennesaw State University.