This week’s writing prompt has me sharing something I wrote during my experience teaching in my first winter residency for the Solstice low-residency MFA program at Pine Manor College. Along with teaching a craft course on poetic authority and hybrid forms and participating in a faculty reading, I also had the privilege of leading a series of graduate workshop sessions with the great poet and educator Kathi Aguero. Together, we led folks in conversations about their respective work as well as discussions on craft, theory, and exercises.

For one exercise, Kathi had us practice writing iambs. My usual practice in freewriting is to be guided by cadence and/or some syllabic or word count concept. Writing into prosody purposefully has always been a misadventure for me; meter is in everything we write (and speak), of course, but I like noting and manipulating its nuances after I have some material written. Only after there is something to work with do I feel comfortable trusting my ear, so to speak.

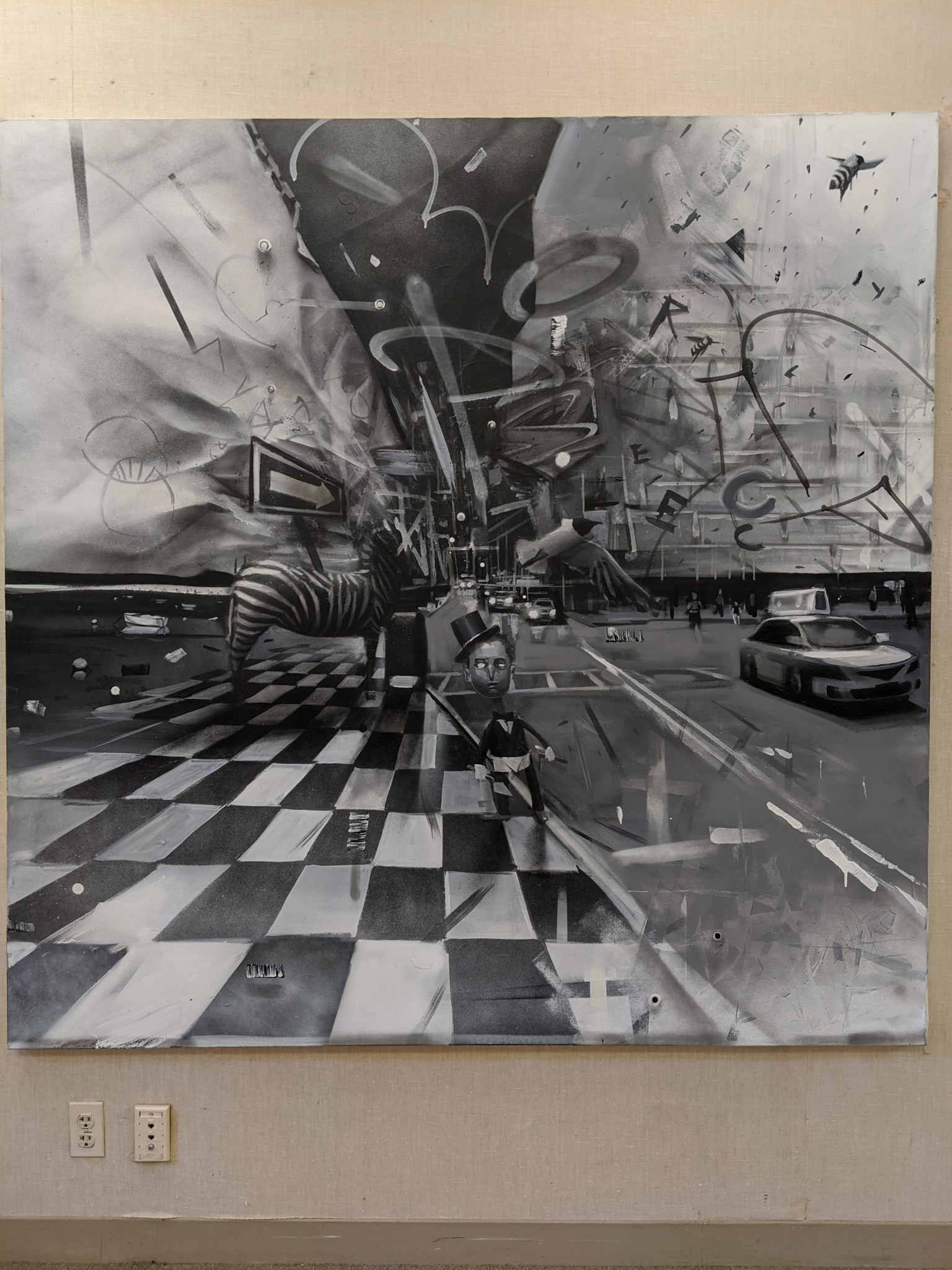

I share about this mistrust of self as a way to explain my thinking (again, after the fact) of how I approached this exercise and happened upon what I’m calling a “found sonnet.” We held our workshops in the library which was featuring a variety of artwork including the piece Mosaic Pavement by Percy Fortini-Wright (see below). Not only was I struck by the dynamic depths and energy of the work itself, I also found myself admiring and nodding my head as I read Fortini-Wright’s statement that accompanied it.

Here’s the statement in full:

As a teacher I sometimes feel as if I’m a student. By this I mean I learn from them as much as they do from me. There is a back-and-forth dialogue which coalesces multiple perspectives in this creative community that we call the classroom. With my background of graffiti and fine arts, I blend both worlds into my teaching philosophy, balancing these two perceived opposites. From this experience of being well-versed in realism and pure abstraction, students obtain a wider bandwidth or perspective to view their work within.

I choose to work in black-and-white using the spray can and brush, and introduced this method to Antonio White, who has taken several of my classes. Spray paint is great for capturing atmospheric qualities of light, haze and distance, while the brush marks and thicker texture appear in the foreground. My black and white painting titled “Mosaic Pavement” embodies many recurring subjects and themes from past paintings: observations, abstract experimentations, passions, and spiritual teachings. The use of opposites can capture the widest range of form, contrast, and dimension, which plays into my constructs both physically and spiritually.

Teaching is legacy where information gets passed down from one generation to the next. That lesson was taught to me from Paul Goodnight, a mentor, friend, and role model to myself, and artists across the world. I met him through mentoring with Paul Rahilly, who I later found out was Paul Goodnight’s teacher, mentor, and dear friend as well. The biggest gifts of teaching are passing on information to the next generation, sharing the experiences of life, and developing long term relationships.

(Percy Fortini-Wright of Pembroke, MA for Mosaic Pavement, Spray and oil paint, 72 x 72 in. 2019)

The artist statement for Mosaic Pavement by Percy Fortini-Wright.

As you can see, Fortini-Wright’s generous vision as an educator and humility in the face of both the creative and teaching task is articulated here in an engaging way. The admiration for this statement led me to naturally begin noting where iambs fell within. I then began singling out phrases in my notebook, keeping them in the order in which they appeared. Since the original exercise was to work in iambs, I decided to suss out as best I could an iambic pentameter line and work out a sonnet from the endeavor.

To try this modified exercise on your own:

- First, find a prose text that you find dynamic. This can be anything from an artist statement as I worked with but also news articles, passages from novels, etc.

- Then, begin noting iambs. If you’re not inclined to work out iambs, feel free to simply curate a series of words and phrases.

- As you select your words and phrases, be sure to keep them in order. The goal is to work out a kind of “ghost” poem from the original.

- When you have fourteen lines that work as a kind of argument, you’ll have your own found sonnet. Note: you don’t have to compose a sonnet from this necessarily. You’re welcome to work out a poem of whatever length and form you desire. The fun, as I see it, comes from working out surprising and parallel statements from the original text.

- Bottom line: Have fun!

Enjoy mine own poem below and feel free to email me with any of your own found sonnets. Happy writing!

A photo of Mosaic Pavement by Percy Fortini-Wright.

José Angel Araguz

Teaching is legacy

(found sonnet based on the artist statement for

Mosaic Pavement by Percy Fortini-Wright)

I sometimes feel as if I’m a student;

I mean I learn from them as they from me.

There is dialogue which coalesces

in this community we call the classroom.

With my background, I blend worlds into

philosophy, balancing opposites.

From this experience of being real,

students band to view their work within.

I choose to work in qualities of light

while recurring subjects abstract passions.

Opposites can capture and construct

both physically and spiritually.

Teaching is legacy: the biggest gifts

are experiences developing.

*

To learn more about the work of Percy Fortini-Wright, go here.