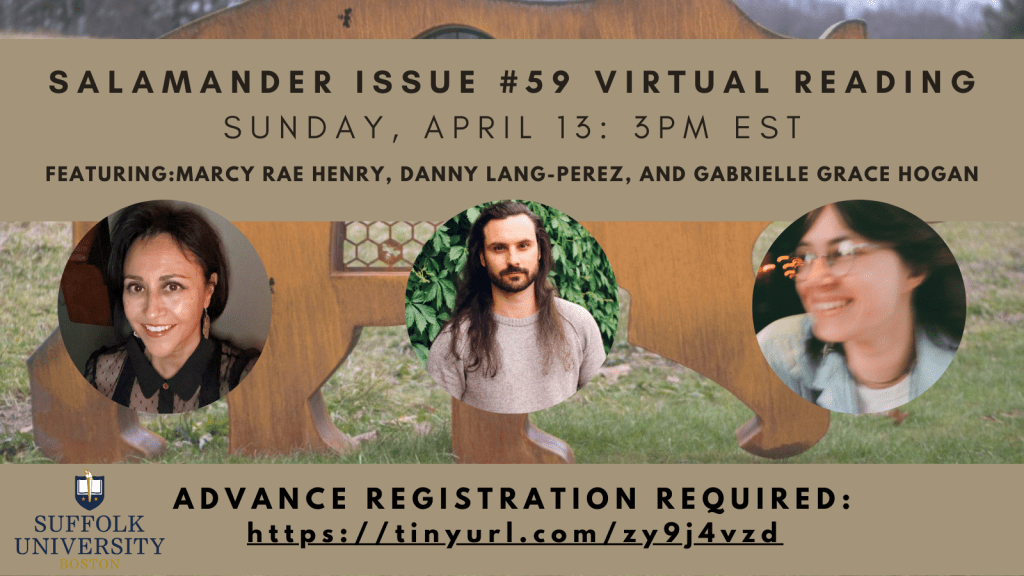

review by José Angel Araguz

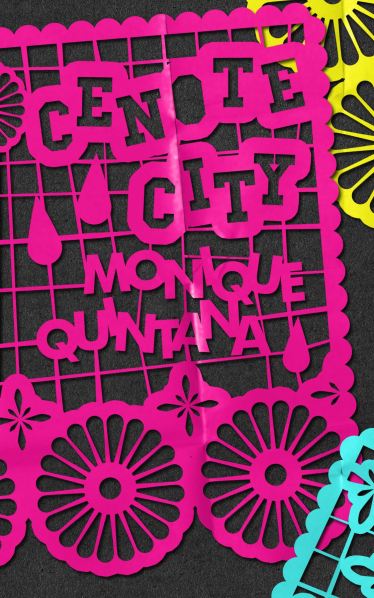

Monique Quintana’s debut novel, Cenote City (Clash Books), is a stellar addition to the Latinx storytelling tradition of texts born out of exploring the intersections where folklore, politics, cultura, and literature meet. Told through fable-like short chapters, Cenote City presents the story of Lune whose mother, Marcrina, cannot stop crying to the point that she has become a tourist attraction, relegated to the nearby cenote, a natural pit or sinkhole that contains groundwater. In the character Marcrina, one can see a variation of the folklore figure of La Llorona (whose own tale has her become a ghost forever crying by the side of rivers after drowning her own children as an act of revenge due to her husband’s infidelity). Quintana draws from this connection and creates a character imbued with a similar sense of sorrow and mortality. What distinguishes Quintana’s Marcrina is the empathetic role she plays in the lives of the community of Cenote City as a deliverer of stillborns. Mediating the humanity of this motherhood experience in one role and serving as a human avatar of endless sorrow in another, Marcrina stands as a symbol of resiliency and depth against The Generales, the police force entity of Cenote City.

Marcrina is just one of a number of characters that inhabit the world of Cenote City; others include a clown able to make children disappear, and a “tiny coven,” one of whom’s members is able to set up a mannequin’s hair into a beehive style and then cast a spell that makes bees appear from it. With radical poetic impulses and flourishes reminiscent of Arthur Rimbaud, Quintana moves the narrative along mainly through the impressions evoked from images and the inner world of her characters. This approach allows her to make full use of the rasquachismo aesthetic, a Chicano sensibility that works to “[transform] social and economic instabilities into a style and a postitive creative attitude.” This aesthetic makes use of collage and places at the forefront the struggle of the oppressed. As a form of storytelling, rasquachismo offers Quintana the use of fruitful and evocative juxtaposition. While this approach at times leads to a dense prose style, the risk is ultimately worth it for how engrossing and captivating the reading experience becomes.

An example of what I mean can be seen in “The Daffodil Dress” (below). In this chapter, readers are presented with a memory of Lune finding Marcrina floating in a pool of water as well as the ensuing panic and recovery. One choice use of juxtaposition occurs around the images of insects coming out of the mother’s mouth. Having insects stand as words in the text lends the narrative a startling new understanding of language. Even when Lune cannot hear what her mother and father say between them, the presence of words is seen as alive and restless.

*

Monique Quintana

The Daffodil Dress

The spring after Lune’s father left them, she found her mother in the backyard of their house, floating in a plastic baby pool, her dress blooming around her body like a daffodil. Lune had been to a birthday party in Storylandia. She began to scream and tried to pull her mother out of the water. The warmth of the water was a shock to her hands and it soaked her party dress, making the skin on her legs burn and itch. She clawed at her own skin with her nails, painted pink by her mother with care. If the clouds could bear witness to that afternoon, they would say that Lune was a swirl of ribbons and brown skin, her kneecaps scraped by the sea of grass, bluish green and bleating, not willing to give up their secrets.

Lune’s screams were loud enough to bring the neighbors, to bring the ambulance, to bring the police, to bring Lune’s father. The paramedic, a young woman with slanted eyes and bright hair administered CPR, while the next-door-neighbor clung to Lune in the sway of bodies, and Lune held her hands in a fist, ready to curse anyone who would let her mother die. The red haired woman hovered over Lune’s mother like she was a kite, blowing the air, willing her to live. Lune’s mother had full round breasts buried under the daffodil dress, and her hair was matted to her mouth like clods of dirt. Lune thought she could see insects fly from her mother’s mouth and ears, when her father appeared and knelt beside her mother and the paramedics. The paramedic’s hands were shaking on Marcrina’s face when Marcrina began to cough up water, the baby pool tipped over and made a bigger pool in the grass, barely touching Lune’s toes again, the tight leather straps of her sandals burning her ankles. She clawed at her own ankles, pulling the sandals off her feet.

Lune thought that her mother had been dead and had been revived because her father had returned to them. There was a tourniquet wrapped around Marcrina’s arm and a stethescope placed at the rise and fall of her breast. Lune thought that her mother’s dying would make her skin turn blue, but it remained as brown as ever, and the daffodil of her dress lay shaking on her hips and her breasts. The paramedics tried to make Lune’s mother go to the hospital, but her father wouldn’t let them take her. He undressed her in the warm glow of the bathroom, the light of the ceiling, making new daffodils on her body. Lune saw her father put her mother in the bathwater, saw him pull her hair away from her face, her shoulder blades shuddered at the touch of the water. Lune could hear them whispering to each other and those whispers became the things that flew out of her mother’s mouth like insects. She tried to make out the lines of the wings and the plump black segments of their bodies, but the insects were hazy and only the buzz of letters could be recognized. No full words. Just moving mouths and shoulder blades and the slow crashing of bathtub water.

After he helped put her mother to bed, Lune’s father heated up cold cocido in a pot and they ate together in their kitchen nook. Lune’s father put his wife’s insects in his mouth and ate them. He ate the secrets and Lune and her father ate the soup together, and they were happy that she wasn’t dead.

*

To learn more about Monique Quintana’s work, visit her site.

Also worth checking out: Blood Moon Blog, where Quintana writes about Latinx literature.

Copies of Cenote City can be purchased from Clash Books.