review by José Angel Araguz

At the end of “Coming of Age in Idaho,” the second poem in Jennifer Met’s chapbook Gallery Withheld (Glass Poetry Press, 2017), the reader is presented with the phrase “an immovable feast” which hearkens back to Ernest Hemingway’s memoir A Moveable Feast. This reference is key on a number of levels beyond wordplay. For one, much of the poems in Met’s book challenge and subvert the very stereotypes and gendered double standards that make possible the aura of a writer like Hemingway. Rather than rail against said aura directly, these poems imply it through sharp insights. As Idaho is “Hemingway country” and the site of his final days, the speaker’s “coming of age” is akin to rising from the ashes of a certain kind of writing tradition and taking flight into another.

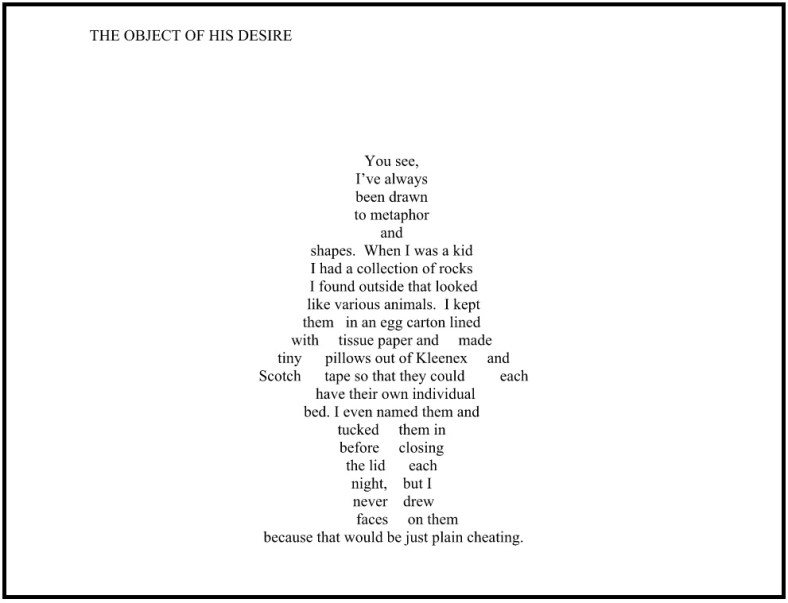

Which is where another level of meaning can be found: this collection brings together lyric poems that trouble traditional poetics through engaging, experimenting, and expanding upon the visual poetry and projective verse traditions. Each poem can be seen as “an immovable feast,” either fixed on the page through intuitive choice or fixed into shape through a formal choice. In “The Object of His Desire,” for example, the narrative of a young boy collecting rocks is troubled when presented in the poetic shape of a woman. This confluence of content and form is purposeful and distinct; if the words were flushed left, they’d still be the same words, but they wouldn’t say the same thing they say in this shape. It is the gift of a visual poem to engage with a language’s plasticity and provide opportunities for multivalent, complex readings. For example, as the poem ends on the idea of facelessness, one can’t help but return to the shape of the poem, and note that where a woman’s face would be are the words: “You see / I’ve always / been drawn / to metaphor.” This implies another facelessness, a societal one. The casual tone of these words further point to the learned narratives of childhood and their insidiousness.

This critique of stereotypes continues in “Old Made: Self-Portrait in a Negative Space,” (below) which lives across from “The Object of His Desire” on the facing page. Where the shape of a woman is the shape of the poem in “Object,” in “Old Made” a woman’s shape is everywhere the poem is not. Even in describing this difference due to formal choice carries with it some of the charged critique that is everywhere in the poem. The assumptions behind the phrase “old maid” are challenged in the title; the rephrasing to “old made” implies how ideas of “old” are “made” in lack of knowledge and lack of connection. It is telling, then, to consider the way this poem ends and begins with the word “Us.” Stereotypes like the one challenged here can make a person feel that they are nothing in the face of others. This feeling is further implied in the form; where the woman’s face would be in this shape, there is instead a list of conjunctions, “if….and….but.” Which is to say that where a face, one’s most personal, recognizable feature, would be, there is instead a brief scatter of words standing alone. Read alone as they are, this list could be read as a half-started, unfinished, and unlistened to protest.

The poems of Gallery Withheld again and again make space to listen and engage with the half-started and unfinished. Reading these poems, one is left like the speaker in “Lefty Loosey” who contemplates Robert S. Neuman’s painting “Monument to No One In Particular” along with another woman who

contemplates

the structure with a frown

and when she leaves I take

her angle hoping

for direction

Each of these immoveable feasts invites the reader to come closer to the text in their reading. And like the speaker above, we must reflect that “its chaos is just / not meant for me or her / or my father in particular / but us all.”

Influence Question: How would you say this collection reflects your idea of what poetry is/can be?

Jennifer Met: I don’t have an MFA and my undergrad degree is in Molecular Biology, so I have a very open opinion of what poetry can be—I am not limited by an idea of what a perfect “workshop” poem should sound like in order to be accepted as real, good poetry. In fact, I am often drawn to forms (like haiku/haibun, speculative, ekphrastic, and concrete poetry) that seem to have more of an outmoded or niche status in the contemporary poetry scene. In a time when poetry has such a limited readership I think it is silly of us to narrow the definition of what poetry can be. I love to read and write widely, and without labels!

In this vein, Gallery Withheld contains poems that have abandoned frames and formal spaces of presentation. They run the gamut from experimental to lyrical to narrative and contain variations of haibun, ekphrastic poems, persona poems, and more. While they share thematic elements exploring definitions of gender, objectification, and the intersection of word, art, and identity, the main binding thread of the collection is that the form of each poem contains some sort of shape/concrete element. More than just a gimmick or a literal, visual shorthand of the content, I think a good shape, like a good title, can lend an extra layer of meaning and engagement to a written piece. It is particularly important in these identity poems as we are so often judged and defined by our visual elements.

For example, take the poem “Object of His Desire” from the collection (originally appearing in experimental poetry journal The Bombay Gin). On the surface it is a charming anecdote about a child keeping pet rocks in an egg carton, but add the shape—an icon—a perfect, bathroom-door skirted woman—and the words become much more sinister. You notice how the rocks are being objectified and their plight becomes symbolic. Sure, they are treated nicely, but are “animals” (implying a hierarchy), and taken care of (again, implying power), named (implying possession and external definition/validity). Then, when the rocks, just like the woman-icon shape, are left without faces, we see how their feelings, even their individuality, ceases to matter. How without eyes, nose and mouth, they are unable to sense stimuli. Static—unable to interact with their environment, process or ever change. Trapped unable to speak and respond. But without any sensory input, they are unaware that this is even an issue—the system feels perpetual, grand, safe, even desirable. Hence the poem becomes the definition of “woman” as seen not just by a man, but by us all—a blank, yet somehow identifiable, object. However, this meaning only exists when the text is paired with the shape.

Influence Question: What were the challenges in writing these poems and how did you work through them?

Jennifer Met: One of the challenges in writing these poems was wrestling with their literally “concrete” nature. Generally I started with an anecdote (narrative or image-based), then formed the polished prose into a meaningful form while trying to be mindful of good line breaks. However, poetry is such a fluid and organic process that this proved limited—the content would inform the shape, which would then re-inform the content, which would then re-inform the shape, in an endless cycle. However, it is not easy to cut or change even a single word without seriously disturbing a set, concrete, typographic shape, so I found myself constantly constructing a shape only to take the writing back out and revise it before reworking it back into a form. Because of this I actually felt the freedom to do a lot more straight-out rewriting than my revisions would usually entail.

Rewriting seems like a lot of work, and even a betrayal of our charged first-words, but it benefitted this collection so much that I have continued the practice in my current poems to great success. While changing single words or just reworking stanza breaks has never been my idea of revision, I have started to really scrap and rebuild poems—often saving only a few phrases, a single image, or even an idea that had unexpectedly developed during its initial writing—a process I highly recommend.

*

Special thanks to Jennifer Met for participating! To find out more about her work, check out her site. Gallery Withheld can be purchased from Glass Poetry Press.

Jennifer Met lives in a small town in North Idaho with her husband and children. She is a Pushcart Prize nominee, a finalist for Nimrod’s Pablo Neruda Prize for Poetry, and winner of the Jovanovich Award. Recent work is published or forthcoming in Gravel, Gulf Stream, Harpur Palate, Juked, Kestrel, Moon City Review, Nimrod, Sleet Magazine, Tinderbox, and Zone 3, among other journals. She is the author of the chapbook Gallery Withheld(Glass Poetry Press, 2017).

Jennifer Met lives in a small town in North Idaho with her husband and children. She is a Pushcart Prize nominee, a finalist for Nimrod’s Pablo Neruda Prize for Poetry, and winner of the Jovanovich Award. Recent work is published or forthcoming in Gravel, Gulf Stream, Harpur Palate, Juked, Kestrel, Moon City Review, Nimrod, Sleet Magazine, Tinderbox, and Zone 3, among other journals. She is the author of the chapbook Gallery Withheld(Glass Poetry Press, 2017).

Jennifer Maritza McCauley is a teacher, writer, and editor living in Columbia, Missouri. She holds or has previously held editorial positions at The Missouri Review, Origins Journal, and The Florida Book Review, amongst other outlets, and has received fellowships from Kimbilio, CantoMundo, the Knight Foundation, and Sundress Academy of the Arts. She is the recipient of an Academy of American Poets University Award and has appeared in Passages North, Puerto del Sol, Split this Rock: Poem of the Week, The Los Angeles Review, Jabberwock Review, and elsewhere. Her collection SCAR ON/SCAR OFF will be published by Stalking Horse Press in fall 2017.

Jennifer Maritza McCauley is a teacher, writer, and editor living in Columbia, Missouri. She holds or has previously held editorial positions at The Missouri Review, Origins Journal, and The Florida Book Review, amongst other outlets, and has received fellowships from Kimbilio, CantoMundo, the Knight Foundation, and Sundress Academy of the Arts. She is the recipient of an Academy of American Poets University Award and has appeared in Passages North, Puerto del Sol, Split this Rock: Poem of the Week, The Los Angeles Review, Jabberwock Review, and elsewhere. Her collection SCAR ON/SCAR OFF will be published by Stalking Horse Press in fall 2017.